Through the Expansive Glass: A Reflection on (Be)longing and Curation at the Völkerkunde Museum

How much of a wall should be cut out to accommodate a window does not always depend upon the purpose of the space or the beings it ought to house.

I did not exactly reach this conclusion the first time I sat inside the Völkerkunde Museum in Heidelberg but for some reason I kept staring at its windows. Expansive and resilient with their wooden frames, the large glass panels seemed to bear the dual responsibility of holding the wall together, along with letting the world in.

Letting the world in must seem like a prerequisite for an ethnographic museum, yet, the Palais Weimer was not originally built as one. Instead, it was a private residence. The expanse of its windows, in that case, was perhaps just a result of pure vanity or perhaps it was the result of a longing to belong to something other than just concrete.

Built between 1710 and 1714, the house at Hauptstraße 235 housed the city’s commander General von Freudenberg-Mariotte. Over the years, the place has undergone numerous transformations which reflects in the way the space appears to be brimming with stories.

One might argue that a museum and a home stand polar opposites to each other in both purpose and presence. A museum emphasizes the material, the curated, and the spectacular, showcasing artifacts and artworks with deliberate intention and careful arrangement. In contrast, a home embodies the lived-in, the ordinary, and the chaotic, serving as a space for personal experiences, everyday activities, and the spontaneous ebb and flow of life.

To me, the Völkerkunde Museum encapsulates both. Amidst its grandeur and extravagance, it also contains rooms filled with chaos and care. Volumes are deftly tucked from floor to ceiling, creating overcrowded spaces that compromise on regulated order for the sake of a distinct coziness. This coziness makes one feel comfortably nestled among books, objects, and artifacts from distant places, some of which one may never have visited. It might all sound seamless as I now describe it but the space is not exactly devoid of struggle. Instead, a conflict for struggle is present in every fabric of its being reflected most strikingly in its resilience to long and belong as the space gets made and unmade through its many lives.

In the 1760s, the house at Hauptstraße 235 briefly served as a kind of production building for the “Zitz (variegated cotton) and cotton factory”. This was during the mercantilist era when rulers bolstered state finances by supporting local manufacturers. However, Heidelberg soon struggled to compete with the burgeoning English weaving industry, and in 1784, the building was repurposed as the seat of the High Cameral School, an agricultural academy relocated from Kaiserslautern. The palace provided classrooms, laboratories, collections, and scientific equipment, while its extensive gardens were ideal for botanical experiments. This college functioned until 1818, after which the “cameral building at the Carlstor” was put up for sale again.

James Mitchell, a merchant from Scotland, acquired the property. Mitchell was an important member of the then “English Colony” in Heidelberg, whose artistic taste was naturally satiated by this baroque palace. After this exclusive phase, Prince Wilhelm Karl Bernhard of Saxony-Weimar-Eisenach acquired the house at Hauptstraße 235 in 1902, and named it the “Palais Weimar”.

In 1921, the palace switched owners once again and was acquired by Victor Goldschmidt and Leontine Goldschmidt, founders of the J. & E. von Portheim Foundation for Science and Art.

The Goldschimts never lived in the Palais Weimar and instead turned it into an ethnographic institute where they housed their diverse collections. The first exhibition of the museum went on display in 1924. Later, the Ethnographic Museum became the only institute to have survived the Nazi era despite being subject to considerable material and immaterial damage.

“Reflecting upon the many lives of the Palais Weimar, I am forced to ponder whether a space loses its essence when it is required to repeatedly redefine its purpose”

Reflecting upon the many lives of the Palais Weimar, I am forced to ponder whether a space loses its essence when it is required to repeatedly redefine its purpose, or does its various incarnations shine through like a palimpsest of belongings? A thing that most likely happens is that the space stops viewing change as a threat and instead looks for ways to challenge the facade of stability that is so often maintained by hierarchies.

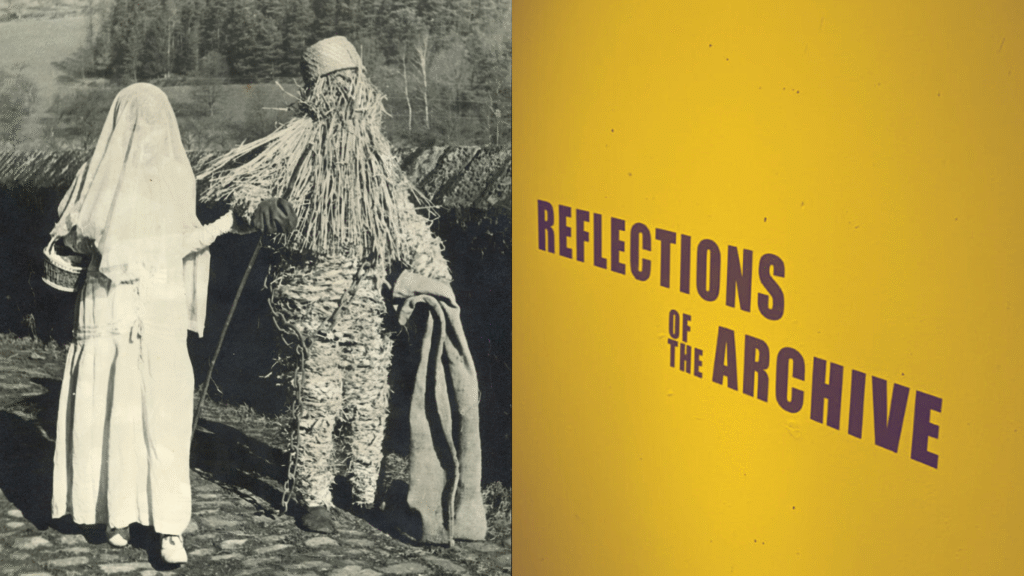

This spirit shines through in the exhibits at the Völkerkunde Museum, which navigate and reflect on the intricate interplay of materiality, history, and culture. One notable exhibit, Reflections of the Archive, collaborates with The Heidelberg Centre for Transcultural Studies, utilizing the perspectives of students to offer fresh approaches to access and present museum archives.

Reflections of the Archive

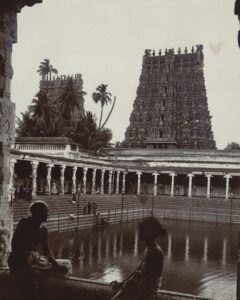

Preserving and presenting photographs from museum archives is almost always a tricky field to navigate as photographs extend beyond mere visual documentation; they encompass the profound understanding of photographs as archival materials, immortalizing moments of the past within museum collections. As repositories of history, these visual materials undergo meticulous conservation efforts, highlighting their dual nature as carriers of memory and physical artifacts.

Exhibiting archival photographs in an ethnographic museum presents an even greater challenge. Historically, the relationship between anthropology and photography is deeply intertwined with colonialism1, making it a contested and complex medium to navigate and reinterpret. Perhaps, this is also a reason why such recontextualization is necessary.

The collection of photographs in Reflections of the Archive were created by different people across different periods and geographies for various purposes. None of them had never been exhibited before, and for several, the details surrounding their creation and acquisition also remain ambiguous. Through the exhibition, they were made accessible to questions surrounding how the materiality, actors and meanings of the photographs transformed over time, what the contemporary insights into photographs might be, how individual perspectives are reflected in the exhibition of the archives, and finally, why some perspectives may be more comprehensible than others. In many ways, revisiting and reinterpreting these archival photos was an attempt to shift the power dynamics surrounding their creation and display.

[Photos of the exhibition]

One way of facilitating this shift was by entrusting the curation to students, primarily from international backgrounds. The curation of Reflections of the Archive was done by 13 students who presented 8 different installations. The photographs themselves were quite diverse, comprising personal albums, family vacation shots, official diplomatic stills, scientific photo-documentation, and ethnographic samples of the ‘exotic’, amongst others.

“…even when the production of the picture is entirely delivered over to the automatism of the camera, the taking of the picture is still a choice involving aesthetic and ethical values.”

French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu is indeed right when he says, “…even when the production of the picture is entirely delivered over to the automatism of the camera, the taking of the picture is still a choice involving aesthetic and ethical values.”2 This choice simultaneously underscores the unequal distribution of power between the photographer and the photographed. Later, the same unequal distribution of power manifests in the realm of the museum when one chooses to exhibit an image. Photography and its subsequent curation thus involves a degree of ethical discipline and responsibility which was reasonably amplified by our own identities of being students and not professionals in the field.

Reflecting on the experience of co-curating this exhibition, I realize that I was initially captivated by the opportunity to work in a museum and learn from professionals. However, on a subconscious level, I was also grappling with the challenge of being an outsider, both in the realm of museum curation and in the country where the curation was taking place. I suppose this abstract feeling of longing and belonging manifested in processes of curation that attempted to move beyond curiosity to reflect responsibility, affect, and power(lessness).

This feeling was shared amongst the other curators as well who articulated this sense of responsibility and how it became central to our curatorial project in the motivation statements that preceded our individual exhibits.

Reflecting on the Exhibition

Reflections of the Archive3 came to life after four months of work to challenge the roles of the curator and the curated, the personal and the public, and the viewer and the receiver. By viewing the archive as a liminal space between memory and forgetting, the exhibition also sought to uncover additional memories that may surface through the act of displaying the archive. To provide more insight, we will now dive into our installations and the motives behind our curations.

Marlies Weileder and Ilknur Erdogan worked on a photograph featuring the Strohnickel and the Christ Child. The photograph at first glance was thought by the students to have been transported from Africa or elsewhere. But it was actually taken very close to Heidelberg, and this misleading first impression forced the curators to repeatedly ask the question, “What do visitors expect from ethnographic collections?” As they traced the photograph’s history, they discovered that the Portheim Foundation, closely associated with Nazi politics in Nazi-era Germany, had obtained this as well as similar images to support and showcase German folklore in its collection. But, being put together with other images —mostly from a colonial past—I, Ilknur, couldn’t differentiate it at the beginning. For me, it was a European bride and a slave man, and the story of this image was an event from a wedding. Reconsidering my shocking mistake, I faced my expectations from an ethnographic collection. Even when looking at a photograph from traditional German folklore, if the people seem unfamiliar, we tend to search for something “ethnic” or “mystical”—often from colonized geographies—in anyone who doesn’t look like a Western man in a suit. I expected to see unequal power relations, social hierarchies, and racial classes from a photograph kept in the museum archive.

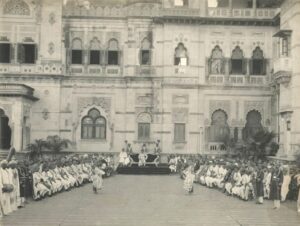

Keeping with the topic of power, race, and gender Kattyayani Tushar Joag, Nikolai Schuhna and I extend a critical lens at the famous Wiele and Klein Photo Studio that operated between 1890 and 1980 in India. Through one photograph that shows Indian women bathing at a local pond, we raised questions about public and private space. Simultaneously, refusing to fall into the common trope of observing women simply as passive actors, we focussed on women’s resistance and, therefore, agency arising from the womens’ discomforted glare in the photograph. In addition, Schuhna was shocked by the dehumanizing note written by an unidentified person on the flipside of another photo featuring a royal event. Collectively we strove to move beyond what an image may depict on the surface to other interpretations that distribute agency and power amongst actors both visible and invisible.

“When a photograph is displayed, who dominates the process of meaning-making central to the image?”

When a photograph is displayed, who dominates the process of meaning-making central to the image? Is it the curators, the subjects in the photographs, or the audience, whose reception and interpretation generate new meanings from the “static” form? Additionally, does the archive’s liminal identity, poised between memory and erasure, also influence the creation and curation of meaning?

Memory and the Archives

Literary theorist and visual artist Aleida Assmann observes memory and archives as both active and passive agents. She writes, “[i]n order to remember anything one has to forget; but what is forgotten is not necessarily lost forever.”4

Reflections of the Archive was profoundly influenced by this interplay of memory and forgetting, as a diverse group of students and educators collaborated to curate this exhibition.

Each individual’s background, upbringing, experiences, and academic perspectives uniquely shaped their formation. The convergence of remembering and forgetting from the curators’ point of view developed through the negotiation of certain memories that could be voiced and others that one was required to let go of.

One significant memory we had to all move past was the dissociation of our exhibition from the Biennale für aktuelle Fotografie, a contemporary photography event based in Germany. Scheduled to open in March 2024 across the cities of Mannheim, Ludwigshafen, and Heidelberg, the Biennale was ultimately canceled by the German government. This decision came in response to social media comments made by Shahidul Alam5, a Bangladeshi photojournalist and co-curator of the event, who condemned Israel’s actions in Gaza following the October 7th attack.

With the cancellation of the Biennale, Reflections of the Archive was opened to the public as a private exhibition of the Völkerkunde Museum on 10th February 2024.

One could say that in the end the event was largely a success. It was visited by several students, professors and guests of Universität Heidelberg and was greatly appreciated. However, it also became a reminder of how much more the exhibition could have been had it opened as a part of the Biennale. Ultimately, it simultaneously highlighted the unequal distribution of power in society—the very power the students had aimed to challenge through their curation.

Conclusion

Reflections of the Archive, both as a project and an exhibition, aimed to cultivate a critical perspective on photography as an archived object in ethnographic museums. Ultimately, it also encouraged a deeper examination of life itself. The exhibition coincidently had its opening exactly a hundred years after the Ethnography Institute’s very first exhibition in 1924. In this sense, as well as others, the Völkerkunde Museum, with its enduring struggle and evolutionary resilience, nurtured this examination of life and art and the ways in which they interfere with each other. Simultaneously, by merging the intimate and the public, the lived-in and the curated, its expansive windows transformed the museum into a space where the walls did more than just hold—they truly let the world in.

Citations

- Cole, Teju. 2019. “When the Camera Was a Weapon of Imperialism. (And When It Still l Is.).” The New York Times Magazine. ↩︎

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1996. Photography : A Middle-Brow Art. Stanford University Press, 6. ↩︎

- “The exhibition focuses on selected photographs from the archive of the Ethnographic Museum vPST. How have the actors, the meaning and the materiality of photography changed over time? What questions and insights can be formulated today on the basis of photographic material from different eras? This experimental exhibition was curated by students and faculty members of the Heidelberg Centre for Transcultural Studies (HCTS).” Taken from https://voelkerkundemuseum-vpst.de/reflections/ ↩︎

- Assmann, Aleida. 2010. “Canon and Archive.” In Cultural Memory Studies: An International and Interdisciplinary Handbook edited by Astrid Erll and Ansgar Nünning, 97-108. De Gruyter. ↩︎

- Shahidul Alam is a Dhaka-based photojournalist, writer and activist. He is the founder of the Drik Picture Library (1989), the Pathshala South Asian Media Institute (1998) and the Chobi Mela International Photography Festival (2000). Alam’s published works include Nature’s Fury (2007), Portraits of Commitment (2009), My Journey as Witness (2011), and Best Years of My Life (2016). Over his career, he has earned numerous accolades, including the Shilpakala Padak awarded by the President of Bangladesh in 2014, the Lucie Awards’ Humanitarian Award in 2018, and the ICP Infinity Award in 2019. Time Magazine named him one of their Persons of the Year in 2018, acknowledging his influence on photojournalism and social activism globally. ↩︎

Quick Explainer In Focus

As its name elucidates, In Focus is a place where we discover topics within the neighbourhood of Heidelberg that delves into the realm of transculturality (but to be fair, everything is transcultural!) We explore how transculturality manifests in our surroundings through interviews on interdisciplinary topics with people in Heidelberg, and will eventually reach out to other regions in the future.