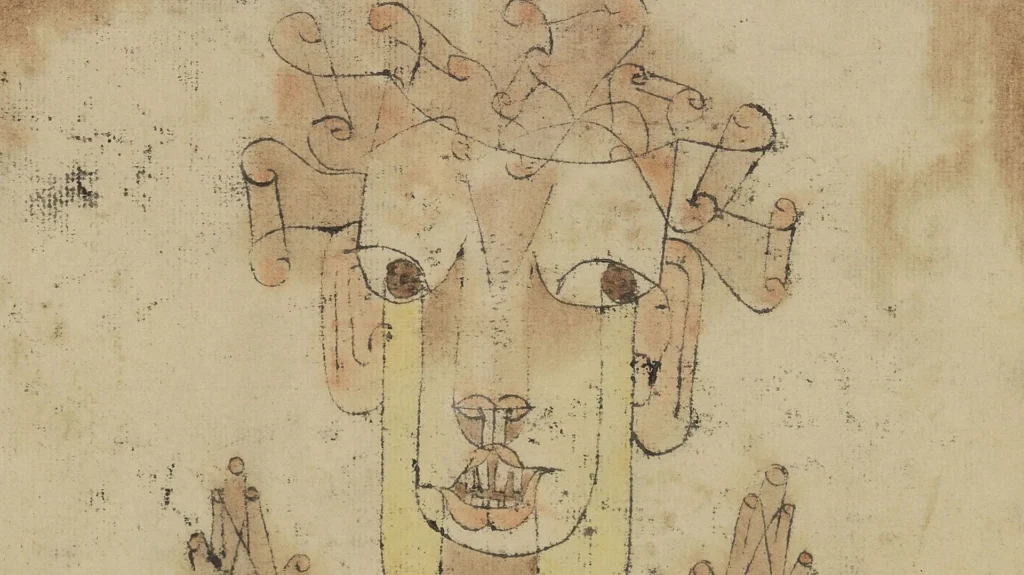

In his essay “Thesis on the Philosophy of History,” philosopher Walter Benjamin describes Paul Klee’s painting Angelus Novus:

“A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”[1]

In an age defined by technological progress accompanied with economic uncertainty which has been escalated due to the pandemic, wars in different parts of the world, and an increase in climate disasters, it is not surprising that people reminiscent to the angel of history are turning their heads to the past and are longing for an age before social media even if the search for this nostalgia is very much facilitated not from memory but from code. Nostalgia, as artist Svetlana Boym writes, “is a sentiment of loss and displacement, but it is also a romance with one’s own fantasy.” She argues that nostalgia is a symptom of modern progress, which thrives in fast-paced technological progress, where the sense of time and self can become disjointed.

It is at this junction of nostalgia and innovation enabled by a gamified social media algorithm that we see the transformation in the creation of cultural content, how it is shared and experienced. While gamified algorithms provide a mechanism for recreating imagined pasts in a dynamic transcultural form, it is the disjoined sense of time which has become the fertile ground for the longing of what sociologist Zygmunt Bauman calls “Retrotopia”.[2] The concept of retrotopia captures a collective longing for the perceived certainties of the past. Unlike utopias, which project ideal societies into the future, retrotopias look backward, framing the past eras as the pinnacle of stability and harmony.

Social media platform designs enable their users to voice a kind of longing, a retrotopian nostalgia which is conjured by code. It’s the mechanism of procedural rhetoric at work that threads us back to a past that feels familiar, even if it never quite existed. Author Ian Bogost defines procedural rhetoric in his book Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames as the ways in which different digital systems, video games[3] in particular, use rules, regulations, mechanics, and interactions to persuade and shape user experience and ideology. On social media platforms, procedural rhetoric reveals itself in platform designs, algorithms, and gamified interactions that subtly guide user behavior.[4]

Facebook’s “On This Day,” Instagram’s “archives”, Snapchat’s “Flashbacks”, all of them conjure a version of our lives that feels more whole than it ever was. They hand us curations, pieces of a story we’re meant to believe, a story that frames the past as something cohesive, something worth longing for. It’s a kind of nostalgia built by the tidy mechanics of code manifested by procedural rhetoric of these platforms.

These features of the platforms do not merely show all memories; it selects those with high engagement. This selection creates a perception of the past as inherently joyful or significant, amplifying retrotopian longing. The procedural framework of these platforms subtly convinces the users that the platform is a vessel for preserving and reliving a better, more authentic era, even if that era is reconstructed and even idealized.

This retrotopian nostalgia is further amplified by the visual cultural aesthetics promoted by the platforms. Retro-inspired filters and challenges such as TikTok trends using 1980s synth music or Instagram filters mimicking vintage film, which creates an emotional link to an imagined past. Another example of visual cultural aesthetics endorsed by platforms that promote a longing for retrotopia is the resurgence of interest in Polaroid photography and cassette tapes. Social media’s procedural rhetoric frames these technologies as symbols of authenticity and simplicity, contrasting them with the perceived complexity and superficiality of the present. This framing persuades users to participate in practices that reconstruct these retrotopian ideals.

Procedural rhetoric plays a key role in promoting and curating filters and challenges. Algorithms prioritize retro-themed content based on user engagement, reinforcing its visibility and appeal. This cyclical process of promotion and interaction persuades users that these nostalgic elements are universally desirable, fostering collective longing for an idealized past.

Platforms like Reddit and Facebook that have a feed sorted algorithmically via a reward system through upvotes or likes foster digital communities that are centered around retrotopian nostalgia. Groups dedicated to sharing vintage photographs, old music, or retro gaming culture use social media’s structural mechanics to create spaces that celebrate the past, which also reinforces the participation and collaboration within these communities. By shaping how users interact and engage with content, procedural systems cultivate an atmosphere where the past is not only remembered but actively idealized.

While the reconstruction of an imagined past is deeply personal, the procedural systems of social media promote the formation of algorithmic tribes which encourages the process of a collective cultural production of these retrotopian ideals which lead to the transculturation of nostalgic elements. The past gets remembered through a hybridized longing nurtured by the mechanics of algorithms.

Digital communities actively merge, reshape and transform imagined histories and identities. The mechanics of the platforms push us together; strangers sharing fragments of a past we’ve never quite lived. Aesthetic gestures like a filtered Polaroid or a soundtrack pulled from a mixtape separate these memories from their realities, sand them down until they can slip easily into the collective imagination. The algorithm, with its ever-increasing appetite for emotion, keeps us coming back. This is how retrotopias emerge, hybrid dreams of a past pieced together from disparate cultures and timelines, freed from linear logic and lived truth. They comfort us, these fictions, even as they dislocate us further, leaving us untethered from any sense of the now.

And yet, here we are, in an age where global loneliness has grown into a shapeless ghost, our dependence on social media is the framework that both holds us up and hems us in. Memory, identity, technology—these threads knot together in ways we barely notice, in ways that demand critical reflection. To engage with the past critically, to reflect instead of merely scrolling, may be the only way to understand the stories we tell ourselves to create a sense of belonging.

[1] Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. Edited by Hannah Arendt. Translated by Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books, 1968

[2] Bauman, Zygmunt. Retrotopia. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017

[3] Verhoef, Shannon. “Play and Metapolitics in Angry Goy II.” Diggit Magazine, June 5, 2019. https://www.diggitmagazine.com/papers/metapolitics-angry-goy-ii

[4] Bogost, Ian. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Video Games. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007